There are two environmental variables that must be defined to run FlightGear. These tell FlightGear where to find it’s data and scenery.

You can set them in a number of ways depending on your platform and requirements.

This is where FlightGear will find data files such as aircraft, navigational beacon locations, airport frequencies. This is the data subdirectory of where you installed FlightGear. e.g. /usr/local/share/FlightGear/data or c:\Program Files\FlightGear\data.

This is where FlightGear will look for scenery files. It consists of a list of directories that will be searched in order. The directories are separated by “:” on Unix and “;” on Windows.

For example, a FG_SCENERY value of

c:\Program Files\FlightGear\data\WorldScenery;c:\Program Files\FlightGear\data\scenery

would search for scenery in

c:\Program Files\FlightGear\data\WorldScenery

first, followed by

c:\Program Files\FlightGear\data\scenery.

This means that you can download different scenery to different locations.

Fig. 3: Ready for takeoff. Waiting at the default startup position at San Francisco Itl., KSFO.

Before you can run FlightGear, you need to have a couple of environmental variables set.

e.g. $FG_ROOT/Scenery:$FG_ROOT/WorldScenery.

To add these in the Bourne shell (and compatibles):

LD_LIBRARY_PATH=/usr/local/share/FlightGear/lib:$LD_LIBRARY_PATH

export LD_LIBRARY_PATH FG_HOME=/usr/local/share/FlightGear export FG_HOME FG_ROOT=/usr/local/share/FlightGear/data export FG_ROOT FG_SCENERY=$FG_ROOT/Scenery:$FG_ROOT/WorldScenery export FG_SCENERY |

or in C shell (and compatibles):

setenv LD_LIBRARY_PATH=\

/usr/local/share/FlightGear/lib:$LD_LIBRARY_PATH setenv FG_HOME=/usr/local/share/FlightGear setenv FG_ROOT=/usr/local/share/FlightGear/data setenv FG_SCENERY=\ $FG_HOME/Scenery:$FG_ROOT/Scenery:$FG_ROOT/WorldScenery |

Once you have these environmental variables set up, simply start FlightGear by running fgfs --option1 --option2…. Command-line options are described in Chapter 3.5.

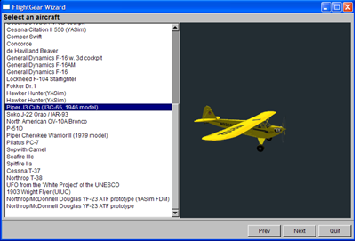

The pre-built windows binaries come complete with a graphical wizard to start FlightGear. Simply double-click on the FlightGear Launcher Start Menu item, or the icon on the Desktop. The launcher allows you to select

The first time your run it, you will be asked to set your FG_ROOT variable (normally c:\Program Files\FlightGear\data) and FG_SCENERY. This should be a list of the directories where you have installed scenery, typically

c:\Program Files\FlightGear\data\scenery

and

c:\Program Files\FlightGear\data\WorldScenery.

If you set invalid values or change your scenery directories later, you can change the settings by pressing the ”Prev” button from the first page of the launcher.

Alternatively, you can run FlightGear from the command line. To do this, you need to set up the FG_ROOT and FG_SCENERY environmental variables manually.

Open a command shell, change to the directory where your binary resides (typically something like c:\Program Files\FlightGear\Win32\bin), set the environment variables by typing

SET FG_HOME=~c:\Program Files\FlightGear~

SET FG_ROOT=~c:\Program Files\FlightGear\data~ SET FG_SCENERY=~c:\Program Files\FlightGear\data\Scenery~;\ ~c:\Program Files\FlightGear\data\WorldScenery~ |

and invoke FlightGear (within the same Command shell, as environment settings are only valid locally within the same shell) via

fgfs --option1 --option2…

Of course, you can create a batch file with a Windows text editor (like notepad) using the lines above.

For getting maximum performance it is recommended to minimize (iconize) the text output window while running FlightGear.

Say, you downloaded the base package and binary to your home directory. Then you can open Terminal.app and execute the following sequence:

setenv FG_ROOT ~/fgfs-base-X.X.X

./fgfs-X.X.X.-date --option1 --option 2 |

or

./fgfs-X.X.X-version-date --fg-root=\~/fgfs-base-X.X.X --option1

|

Following is a complete list and short description of the numerous command line options available for FlightGear. Most of these options are exposed through the FlightGear launcher delivered with the Windows binaries.

If you have options you re-use continually, you can include them in a preferences file. As it depends on your preferences, it is not delivered with FlightGear, but can be created with any text editor (notepad, emacs, vi, if you like).

Shows the most relevant command line options only.

Shows all command line options.

Tells FlightGear where to look for its root data files if you didn’t compile it with the default settings.

Allows specification of a path to the base scenery path , in case scenery is not at the default position under $FG ROOT/Scenery; this might be especially useful in case you have scenery on a CD-ROM.

Enables full screen display.

Turns off the rotating 3DFX logo when the accelerator board gets initialized (3DFX only).

If you like advertising, set this!

No audio sample is being played when FlightGear starts up. Suggested in case of trouble with playing the intro.

If your machine is powerful enough, enjoy this setting.

Enables extra mouse pointer. Useful in full screen mode for old Voodoo based cards.

Include random scenery objects (buildings/trees). This is the default.

Exclude random scenery objects (buildings/trees).

This will put you into FlightGear with the engine running, ready for Take-Off.

Fuel is consumed normally.

Fuel tank quantity is forced to remain constant.

Time of day advances normally.

Do not advance time of day.

Specify your control device (joystick, keyboard, mouse) Defaults to joystick (yoke).

Switches auto coordination between aileron/rudder off (default).

Switches auto coordination between aileron/rudder on (recommended without pedals).

specify location of your web browser. Example: --browser-app=

”C:\Program Files\Internet Explorer\iexplore.exe”

(Note the ” ” because of the spaces!).

set property name to value

Example: --prop:/engines/engine0/running=true for starting

with running engines. Another example:

--aircraft=c172

--prop:/consumables/fuels/tank[0]/level-gal=10

--prop:/consumables/fuels/tank[1]/level-gal=10

filles the Cessna for a short flight.

Load additional properties from the given path. Example:

fgfs --config=./Aircraft/X15-set.xml

Use feet for distances.

Synchronize time with real-world time

Synchronize time with local real-world time

Specify a starting date/time with respect to system time

Specify a starting date/time with respect to Greenwich Mean Time

Specify a starting date/time with respect to Local Aircraft Time

--time-match-real, basically gives our initial behavior: Simulator time is read from the system clock, and is used as is. When your virtual flight is in the same timezone as where your computer is located, this may be desirable, because the clocks are synchronized. However, when you fly in a different part of the world, it may not be the case, because there is a number hours difference, between the position of your computer and the position of your virtual flight.

The option --time-match-local takes care of this by computing the timezone difference between your real world time zone and the position of your virtual flight, and local clocks are synchronized.

The next three options are meant to specify the exact startup time/date. The three functions differ in that the take either your computer systems local time, greenwich mean time, or the local time of your virtual flight as the reference point.

Each of these five options were designed to be used exclusively, however, the value set by these functions could be modified using the --time-offset function. The latter would add a specified amount of time to the value already set by the other functions.

Enable screen shot http server on the specified port.

Enables Oliver Delises’s multi-pilot mode.

Disables Oliver Delises’s multi-pilot mode (default).

HUD displays network info.

Allows specifying a waypoint for the GC autopilot; it is possible to specify multiple waypoints (i.eȧ route) via multiple instances of this command.

This is more comfortable if you have several waypoints. You can specify a file to read them from.

Note: These options are rather geared to the advanced user who knows what he is doing.

Open connection using the Garmin GPS protocol.

Open connection to an Agwagon joystick.

Open connection using the FG native Controls protocol.

Open connection using the FG Native FDM protocol.

Open connection using the FG Native protocol.

Open connection using the NMEA protocol.

Open connection using the OpenGC protocol.

Open connection using the interactive property manager.

Open connection using the PVE protocol.

Open connection using the RayWoodworth motion chair protocol.

Open connection using the RUL protocol.

Enable atc610x interface.

Trace the reads for a property; multiple instances are allowed.

Trace the writes for a property; multiple instances are allowed.

Could you imagine a pilot in his or her Cessna controlling the machine with a keyboard alone? For getting the proper feeling of flight you will need a joystick/yoke plus rudder pedals, right? However, the combination of numerous types of joysticks, flightsticks, yokes, pedals etcȯn the market with the several target operating systems, makes joystick support a nontrivial task in FlightGear.

FlightGear has integrated joystick support, which automatically detects any joystick, yoke, or pedals attached. Just try it! If this does work for you, lean back and be happy! You can see what FlightGear has detected your joystick as by selecting Help -> Joystick Information from the menu.

Unfortunately, given the several combinations of operating systems supported by FlightGear (possibly in foreign languages) and joysticks available, chances are your joystick does not work out of the box. Basically, there are two alternative approaches to get it going, with the first one being preferred.

In order for joystick auto-detection to work, a joystick bindings xml file must exist for each joystick. This file describes what axes and buttons are to be used to control which functions in FlightGear. The associations between functions and axes or buttons are called “bindings”. This bindings file can have any name as long as a corresponding entry exists in the joysticks description file

/FlightGear/joysticks.xml

which tells FlightGear where to look for all the bindings files. We will look at examples later.

FlightGear includes several such bindings files for several joystick manufacturers in folders named for each manufacturer. For example, if you have a CH Products joystick, look in the folder

/FlightGear/Input/Joysticks/CH

for a file that might work for your joystick. If such a file exists and your joystick is working with other applications, then it should work with FlightGear the first time you run it. If such a file does not exist, then we will discuss in a later section how to create such a file by cutting and pasting bindings from the examples that are included with FlightGear.

Does your computer see your joystick? One way to answer this question under Linux is to reboot your system and immediately enter on the command line

dmesg | grep Joystick

which pipes the boot message to grep which then prints every line in the boot message that contains the string “Joystick”. When you do this with a Saitek joystick attached, you will see a line similar to this one:

input0: USB HID v1.00 Joystick [SAITEK CYBORG 3D USB] on usb2:3.0

This line tells us that a joystick has identified itself as SAITEK CYBORG 3D USB to the operating system. It does not tell us that the joystick driver sees your joystick. If you are working under Windows, the method above does not work, but you can still go on with the next paragraph.

FlightGear ships with a utility called js demo. It will report the number of joysticks attached to a system, their respective “names”, and their capabilities. Under Linux, you can run js demo from the folder /FlightGear/bin as follows:

$ cd /usr/local/FlightGear/bin

$  js demo

js demo

Under Windows, open a command shell (Start All Programs

All Programs Accessories), go to the

FlightGear binary folder and start the program as follows (given FlightGear is installed

under c:\Flightgear)

Accessories), go to the

FlightGear binary folder and start the program as follows (given FlightGear is installed

under c:\Flightgear)

cd \FlightGear\bin

js demo.exe

On our system, the first few lines of output are (stop the program with  C if it is

quickly scrolling past your window!) as follows:

C if it is

quickly scrolling past your window!) as follows:

Joystick test program.

Joystick 0: “CH PRODUCTS CH FLIGHT SIM YOKE USB ”

Joystick 1: “CH PRODUCTS CH PRO PEDALS USB”

Joystick 2 not detected

Joystick 3 not detected

Joystick 4 not detected

Joystick 5 not detected

Joystick 6 not detected

Joystick 7 not detected

+——————–JS.0———————-+——————–JS.1———————-+

| Btns Ax:0 Ax:1 Ax:2 Ax:3 Ax:4 Ax:5 Ax:6 | Btns Ax:0 Ax:1 Ax:2 |

+———————————————-+———————————————-+

| 0000 +0.0 +0.0 +1.0 -1.0 -1.0 +0.0 +0.0 . | 0000 -1.0 -1.0 -1.0 . . . . . |

First note that js demo reports which number is assigned to each joystick recognized by the driver. Also, note that the “name” each joystick reports is also included between quotes. We will need the names for each bindings file when we begin writing the binding xml files for each joystick.

Axis and button numbers can be identified using js demo as follows. By observing the output of js demo while working your joystick axes and buttons you can determine what axis and button numbers are assigned to each joystick axis and button. It should be noted that numbering generally starts with zero.

The buttons are handled internally as a binary number in which bit 0 (the least significant bit) represents button 0, bit 1 represents button 1, etc., but this number is displayed on the screen in hexadecimal notation, so:

0001 ⇒ button 0 pressed

0002 ⇒ button 1 pressed

0004 ⇒ button 2 pressed

0008 ⇒ button 3 pressed

0010 ⇒ button 4 pressed

0020 ⇒ button 5 pressed

0040 ⇒ button 6 pressed

... etc p to ...

p to ...

8000 ⇒ button 15 pressed

... and ...

0014 ⇒ buttons 2 and 4 pressed simultaneously

... etc.

For Linux users, there is another option for identifying the “name” and the numbers assigned to each axis and button. Most Linux distributions include a very handy program, “jstest”. With a CH Product Yoke plugged into the system, the following output lines are displayed by jstest:

jstest /dev/js3

Joystick (CH PRODUCTS CH FLIGHT SIM YOKE USB ) has 7 axes and 12 buttons. Driver version is 2.1.0

Testing…(interrupt to exit)

Axes: 0: 0 1: 0 2: 0 3: 0 4: 0 5: 0 6: 0 Buttons: 0:off 1:off 2:off 3:on 4:off 5:off 6:off 7:off 8:off

9:off 10:off 11:off

Note the “name” between parentheses. This is the name the system associates with your joystick.

When you move any control, the numbers change after the axis number corresponding to that moving control and when you depress any button, the “off” after the button number corresponding to the button pressed changes to “on”. In this way, you can quickly write down the axes numbers and button numbers for each function without messing with binary.

At this point, you have confirmed that the operating system and the joystick driver both recognize your joystick(s). You also know of several ways to identify the joystick “name” your joystick reports to the driver and operating system. You will need a written list of what control functions you wish to have assigned to which axis and button and the corresponding numbers.

Make the following table from what you learned from js demo or jstest above (pencil and paper is fine). Here we assume there are 5 axes including 2 axes associated with the hat.

| Axis | Button |

| elevator = 0 | view cycle = 0 |

| rudder = 1 | all brakes = 1 |

| aileron = 2 | up trim = 2 |

| throttle = 3 | down trim = 3 |

| leftright hat = 4 | extend flaps = 4 |

| foreaft hat = 5 | retract flaps = 5 |

| decrease RPM = 6 | |

| increase RPM = 7 |

We will assume that our hypothetical joystick supplies the “name” QUICK STICK 3D USB to the system and driver. With all the examples included with FlightGear, the easiest way to get a so far unsupported joystick to be auto detected, is to edit an existing binding xml file. Look at the xml files in the sub-folders of /FlightGear/Input/Joysticks/. After evaluating several of the xml binding files supplied with FlightGear, we decide to edit the file

/FlightGear/Input/Joysticks/Saitek/Cyborg-Gold-3d-USB.xml.

This file has all the axes functions above assigned to axes and all the button functions above assigned to buttons. This makes our editing almost trivial.

Before we begin to edit, we need to choose a name for our bindings xml file, create the folder for the QS joysticks, and copy the original xml file into this directory with this name.

$ cd /usr/local/FlightGear/Input/Joysticks

$ mkdir QS

$ cd QS

$ cp /usr/local/FlightGear/Input/Joysticks/Saitek/

Cyborg-Gold-3d-USB.xml QuickStick.xml

Here, we obviously have supposed a Linux/UNIX system with FlightGear being installed under /usr/local/FlightGear. For a similar procedure under Windows with FlightGear being installed under c:FlightGear, open a command shell and type

c:

cd /FlightGear/Input/Joysticks

mkdir QS

cd QS

copy /FlightGear/Input/Joysticks/Saitek/

Cyborg-Gold-3d-USB.xml QuickStick.xml

Next, open QuickStick.xml with your favorite editor. Before we forget to change the joystick name, search for the line containing <name>. You should find the line

<name>SAITEK CYBORG 3D USB</name>

and change it to

<name>QUICK STICK 3D USB</name>.

This line illustrates a key feature of xml statements. They begin with a <tag> and end with a </tag>.

You can now compare your table to the comment table at the top of your file copy. Note that the comments tell us that the Saitek elevator was assigned to axis 1. Search for the string

<axis n=~1~>

and change this to

<axis n=~0~>.

Next, note that the Saitek rudder was assigned to axis 2. Search for the string

<axis n=~2~>

and change this to

<axis n=~1~>.

Continue comparing your table with the comment table for the Saitek and changing the axis numbers and button numbers accordingly. Since QUICKSTICK USB and the Saitek have the same number of axes but different number of buttons, you must delete the buttons left over. Just remember to double check that you have a closing tag for each opening tag or you will get an error using the file.

Finally, be good to yourself (and others when you submit your new binding file to a FlightGear developers or users archive!), take the time to change the comment table in the edited file to match your changed axis and button assignments. The new comments should match the table you made from the js demo output. Save your edits.

Several users have reported that the numbers of axes and buttons assigned to functions may be different with the same joystick under Windows and Linux. The above procedure should allow one to easily change a binding xml file created for a different operating system for use by their operating system.

Before FlightGear can use your new xml file, you need to edit the file

/FlightGear/joysticks.xml,

adding a line that will include your new file if the “name” you entered between the name tags matches the name supplied to the driver by your joystick. Add the following line to joysticks.xml.

<js-named include=~Input/Joysticks/QS/QuickStick.xml~/>

You can tell how FlightGear has interpretted your joystick setup by selecting Help -> Joystick Information from the Menu.

Basically, the procedures described above should work for Windows as well. If your joystick/yoke/pedals work out of the box or if you get it to work using the methods above, fine. Unfortunately there may be a few problems.

The first one concerns users of non-US Windows versions. As stated above, you can get the name of the joystick from the program js demo. If you have a non-US version of Windows and the joystick .xml files named above do not contain that special name, just add it on top of the appropriate file in the style of

<name>Microsoft-PC-Joysticktreiber </name>

No new entry in the base joysticks.xml file is required.

Unfortunately, there is one more loophole with Windows joystick support. In case you have two USB devices attached (for instance a yoke plus pedals), there may be cases, where the same driver name is reported twice. In this case, you can get at least the yoke to work by assigning it number 0 (out of 0 and 1). For this purpose, rotate the yoke (aileron control) and observe the output of js demo. If figures in the first group of colons (for device 0) change, assignment is correct. If figures in the second group of colons (for device 1) change, you have to make the yoke the preferred device first. For doing so, enter the Windows “Control panel”, open “Game controllers” and select the “Advanced” button. Here you can select the yoke as the “Preferred” device. Afterward you can check that assignment by running js demo again. The yoke should now control the first group of figures.

Unfortunately, we did not find a way to get the pedals to work, too, that way. Thus, in cases like this one (and others) you may want to try an alternative method of assigning joystick controls.

Fortunately, there is a tool available now, which takes most of the burden from the average user who, maybe, is not that experienced with XML, the language which these files are written in.

For configuring your joystick using this approach, open a command shell (command prompt under windows, to be found under Start|All programs|Accessories). Change to the directory /FlightGear/bin via e.g. (modify to your path)

cd c:\FlightGear\bin

and invoke the tool fgjs via

./fgjs

on a UNIX/Linux machine, or via

fgjs

on a Windows machine. The program will tell you which joysticks, if any, were detected. Now follow the commands given on screen, i.eṁove the axis and press the buttons as required. Be careful, a minor touch already “counts” as a movement. Check the reports on screen. If you feel something went wrong, just re-start the program.

After you are done with all the axis and switches, the directory above will hold a file called fgfsrc.js. If the FlightGear base directory FlightGear does not already contain an options file .fgfsrc (under UNIX)/system.fgfsrc (under Windows) mentioned above, just copy

fgfsrc.js into .fgfsrc (UNIX)/system.fgfsrc (Windows)

and place it into the directory FlightGear base directory FlightGear. In case you already wrote an options file, just open it as well as fgfsrc.js with an editor and copy the entries from fgfsrc.js into .fgfsrc/system.fgfsrc. One hint: The output of fgjs is UNIX formatted. As a result, Windows Editor may not display it the proper way. I suggest getting an editor being able to handle UNIX files as well (and oldie but goldie in this respect is PFE, just make a web search for it). My favorite freeware file editor for that purpose, although somewhat dated, is still PFE, to be obtained from

http://www.lancs.ac.uk/people/cpaap/pfe/.

The the axis/button assignment of fgjs should, at least, get the axis assignments right, its output may need some tweaking. There may be axes moving the opposite way they should, the dead zones may be too small etc. For instance, I had to change

–prop:/input/joysticks/js[1]/axis[1]/binding/factor=-1.0

into

–prop:/input/joysticks/js[1]/axis[1]/binding/factor=1.0

(USB CH Flightsim Yoke under Windows XP). Thus, here is a short introduction into the assignments of joystick properties.

Basically, all axes settings are specified via lines having the following structure:

--prop:/input/joysticks/js[n]/axis[m]/binding

/command=property-scale (one line)

--prop:/input/joysticks/js[n]/axis[m]/binding

/property=/controls/steering option (one line)

--prop:/input/joysticks/js[n]/axis[m]/binding

/dead-band=db (one line)

--prop:/input/joysticks/js[n]/axis[m]/binding

/offset=os (one line)

--prop:/input/joysticks/js[n]/axis[m]/binding

/factor=fa (one line)

where

| n | = | number of device (usually starting with 0) |

| m | = | number of axis (usually starting with 0) |

| steering option | = | elevator, aileron, rudder, throttle, mixture, pitch |

| dead-band | = | range, within which signals are discarded; |

| useful to avoid jittering for minor yoke movements | ||

| offset | = | specifies, if device not centered in its neutral position |

| factor | = | controls sensitivity of that axis; defaults to +1, |

| with a value of -1 reversing the behavior |

You should be able to at least get your joystick working along these lines. Concerning all the finer points, for instance, getting the joystick buttons working, John Check has written a very useful README being included in the base package to be found under FlightGear/Docs/Readme/Joystick.html. In case of any trouble with your input device, it is highly recommended to have a look into this document.